1-Maximise live calves

Maximise the number of live calves per breeding female

Manage cows and heifers for high fertility to maximise the lives calves per breeding female.

Guidelines for managing cows to achieve high fertility

Profitability in beef production is driven by high stocking rate and high herd fertility, which are both a function of high feed quality and quantity (dry matter production).

Fertility

In a fertile herd, 70% of exposed females will be cycling, exhibiting oestrus and becoming pregnant in the first oestrous cycle; more than 95% will be pregnant at the end of the second oestrous cycle (ie after 6 weeks).

The basic components of herd fertility are:

- calving heifers at two years old

- high pregnancy rates in all age groups

- a short calving span

- a concentrated calving pattern within span

- minimising dystocia losses in two-year-old heifers

- getting first-calvers back in calf quickly.

Nutrition

Nutrition is the key to understanding what really drives efficient reproduction. Nutrition influences the onset of puberty in heifers, and the ability to exhibit oestrus and get in calf quickly, either as heifers or return to oestrus post-calving in first calf heifers.

The key indicators of reproductive performance are body condition score for cows and liveweight for heifers.

Adequate nutrition (principally energy) over and above maintenance and growth requirements is required to drive the onset of oestrus, both in young growing heifers and older cows. Older cattle that have no growth requirements can allocate more energy to reproductive processes than rapidly growing heifers, who have high energy and protein requirements for growth.

The energy intake for pregnant heifers must always be adequate to maintain growth for herself, and for the developing gravid uterus. This requirement has been quoted as being around 40MJ for maintenance and 34MJ for each kilogram of body weight gained by the heifer in the growing stage to the point of calving. The developing foetus requires an extra 5MJ/day for the first five months pregnancy, 8MJ/day at six months pregnancy, 11MJ/day at seven months, 15MJ/day at eight months and 20MJ/day at nine months pregnancy.

| Breeder cows | 350kg | 400kg | 450kg | 500kg | 550kg | Protein required |

| Dry cow | 48 | 52 | 57 | 61 | 66 | 6% |

| Pregnant, last 3 months | 60 | 65 | 69 | 74 | 78 | 6% |

| Lactating cow and calf, 0–3 months | 74 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 | 10–11% |

| Lactating cow and 150kg calf (using DSE ratings in PROGRAZE) | 111 | 118 | 125 | 133 | 140 | 10–11% |

| Growing cattle | 150kg | 200kg | 300kg | 400kg | 500kg | Protein required |

| Maintenance | 22 | 26 | 35 | 45 | 55 | 8% |

| Gaining 0.5kg/day | 37 | 44 | 57 | 71 | 82 | 10–12% |

| Gaining 1.0kg/day | 50 | 59 | 76 | 93 | 108 | 13% |

Older cattle may have body reserves that can be used in times of energy deficit. The loss of 1kg of body weight will release around 29MJ of energy that can be allocated to the reproductive process over and above what has been consumed.

Controlled weight loss at certain times of the year is acceptable, as long as it does not impinge on biological function. For older cows, body condition score may fall as much as 1.5 units, say from condition score 4.0 in late spring after they have grazed the spring flush to a condition score 2.5 by winter. This equates to a 110kg weight loss, or a release of 3,000MJ of energy from fat without any undue side effects, if done correctly. The ability to 'mine' the body condition of cows is a great tool in shifting the pasture curve, but it requires careful management not to exceed the biological constraints and impinge on reproductive ability.

This explains why body condition score is an important factor in determining return to oestrus if feed consumed daily is not meeting total energy requirements.

Conversely, even when body condition score may appear inadequate, if high quality feed is on offer – over and above that required for growth and maintenance – adequate energy can be redirected to the reproductive process.

Body condition score is a retrospective measure, and current feed conditions must also be considered.

It is more accurate to calculate daily intake (MJ consumed) and match this to daily energy requirements (MJ required) of a particular stock class to achieve a predetermined outcome. This also allows proactive management of risk when feed is limiting.

Guidelines for heifer management and nutrition

Management for joining first-calf heifers and their subsequent performance is entirely governed by controlling the body weight from pre-weaning through post-weaning to joining, and then from joining to calving.

Onset of puberty

Puberty is a function of both genetic makeup and biological constraints. Of the biological constraints, nutrition, body weight and age play a greater role in determining the onset of puberty than age alone.

Table 2 demonstrates that by increasing growth rate through good nutrition, puberty is reached earlier and faster, but at the same weight as the slow growing heifers. That is to say, fast growing Holstein heifers reach puberty at the same liveweight as slow growing heifers.

| Growth rates | Daily gain to puberty | Age at puberty | Weight at puberty | % of mature weight at puberty |

| Slow | 0.41 | 20.2 | 289 | 43 |

| Medium | 0.67 | 11.2 | 265 | 39 |

| Fast | 0.72 | 9.2 | 278 | 40 |

In beef breeds, puberty occurs when heifers reach about 52% of mature body weight. The recommended critical mating weight is 55–60% of mature body weight but this varies depends on frame score and individual breed.

| Age at puberty | Weight | |

| Hereford | 13.9 months | 285kg |

| Angus | 12.8 months | 270kg |

Critical mating weight (CMW) for heifers

Adopting the concept of a target weight for joining that exceeds the weight required for the onset of puberty will ensure that all heifers are actively cycling and fully fertile when exposed to a bull. A target of 65–70% is easily achievable and will ensure that the maximum number of heifers conceive in the first oestrus cycle during the joining period. This will also create a concentrated calving pattern over a short timeframe, an even drop of calves and, most importantly for the calved heifer, a better chance of returning to oestrus to maintain a 365-day calving interval.

Management of heifers from weaning to joining to reach critical mating weight (CMW)

Critical mating weight is defined as the weight at which 85% of heifers fall pregnant over 45 days (two cycles).

- Weigh heifers every 6 weeks after weaning to stay on growth targets.

- Use supplementary feed to attain growth (as a guide, feed 1% body weight in silage, hay or grain to supplement pasture).

- Formulate feeding strategies well in advance of joining to reach critical mating weight.

- Practice good parasite control at weaning (an often neglected aspect) using an effective drench, and drench again 3–4 weeks prior to joining.

- Ensure all heifers are cycling in unison before mating because fertility at first oestrus is 21% lower than at third oestrus.

- Supplement with selenium to improve reproductive efficiency and achieve high conception rates, if deficient.

- Maximise the number of heifers reaching critical mating weight 2–3 cycles before joining.

Importance of a tight calving span in heifers and cowsHow a heifer calves in her first gestation in relation to the herd calving span determines the relationship of that cow to the herd for the rest of her life. Heifers who calve early in the calving season will continue to do so for the rest of their life. Tight calving spans allow even calf drops, even lines of saleable cattle, better management, better use of labour and a herd that consistently reproduces within a 365-day timeframe. In two studies, early calving heifers had, on average, weaned calves for the rest of their lives that were 13kg heavier than their herd mates who calved in cycles 3-4 as heifers. Trial resultsInfluence of calving date on subsequent fertility

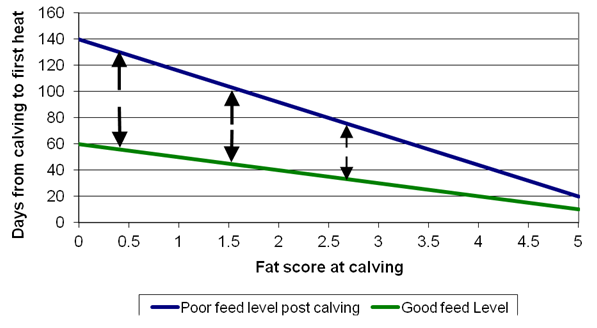

It is critical to continue growing heifers from joining to calving to obtain maximum pelvic size for the calving process. Heifer condition score and energy intake at calving determines the ability to return to oestrus and maintain a 365-day calving interval. Cattle that calve in low body score but have good nutrition post-calving (spring calving) will return to oestrus. The problem of low body score at calving is offset to some extent by the increasing plane of nutrition. Cattle with a low body score at calving and then poor nutrition post-calving will fail to cycle (autumn calving). |

Use cow condition score and heifer liveweight as indicators of herd fertility

Guidelines for the minimum and maximum mating values for British breed heifers and cows

Minimum mating values

- For heifers – joining liveweight of 300kg, condition score 3.0 at 15 months of age (see Tool 5.1 for a guide to minimum joining liveweight).

- For mature cows – condition score 2.5 (see Tool 5.2) with increasing plane of nutrition post-calving.

- For first-calf heifers – condition score 3.0.

Maximum mating values

- Condition score 3.5.

If the breeding herd is outside these recommended guidelines:

- increase or decrease pasture available or pasture quality before mating to ensure condition score of cows or liveweight of weaner heifers remains within the recommended limits.

- wean calves when cow condition score falls to 2.5 (trigger threshold) as long as calves are older than 120 days or at minimum 100kg liveweight.

- supplementary feed a high quality diet to cows when condition score is below 2.0.

- supplementary feed heifers if required, with known energy density feed to ensure they reach target weight, and consider including the use of a rumen non-degradable protein source if pasture quality is low (see Tool 5.1).

- Assess animal health status, particularly for internal parasites (worms, fluke), and treat if there is a problem as described in Module 6: Herd health and welfare.

- Cull weaner heifers that fail to reach target liveweight or conceive within two mating cycles.

Genetics, as reflected through various EBVs, also has a minor role in breeding for herd fertility:

- Selecting sires with a high EBV for scrotal circumference results in earlier onset of puberty in the heifers.

- Days to calving EBV will also help in decreasing the interval between calving and conception by decreasing the gestational length.

- Calving difficulties are reduced by selecting sires with a low score EBV for gestation length.

- Low EBV for birthweight will decrease calf size for that generation but should be used cautiously as most cases of dystocia are a result of a failure to maximise maternal pelvic size through poor nutritional management. Managing nutrition is a far more immediate way to manage calving ease.

- If the phenotype of the herd, especially heifers, is high yielding with a larger mature body size (ie Euro type), they tend to be later maturing with a later onset of oestrus.

Use Tool 3.5 of Module 3: Pasture Utilisation as the basis for determining how pasture can be successfully turned into animal products to profit the farm business. Strategies in Module 3: Pasture Utilisation enable you to more precisely manage the conversion of pasture energy and nutrients to saleable beef product while leaving pasture residue in an optimum condition for rapid regrowth. It also better matches the seasonal feed supply with beef enterprise opportunities and business objectives.

Manage fertility to maintain a calving interval < 365 days

Calving to conception interval

The time between calving and conception has a major impact on the reproductive performance of beef herds and cows must mate by around day 82 after calving if the mean calving time is to remain the same from year-to-year with a 365-day calving interval.

The inability to maintain a 365-day interval will invariably mean a drift in the mean calving date later and as a result the calving histogram will change, more late calves born, more cows fail to join on the next joining and drop out empty. The late drop calves have less growing days to weaning, lighter selling weights and more heifers unable to reach the critical mating weight with less growing days.

There is strong evidence that body weight and particularly body condition score of cows at calving has a substantial effect on the post-partum anoestrus interval. Increases in condition score during late pregnancy through the provision of good nutrition, particularly energy, can reduce the interval between calving and first oestrus for all cows except those in good condition where it has no effect. A similar outcome can be achieved through the provision of good nutrition during early lactation.

The target condition score at calving will depend on the quantity and quality of available pasture after calving and the timing of calving relative to other cows in the herd. Using the Australian cattle condition score system from 0.0 to 5.0, early calving mature cows should have a condition score of 2.0–2.5, late calving cows a score of 3.0–3.5 and early calving first calf cows a score of 2.5–3.0. For cows with a condition score less than that prescribed, the provision during late pregnancy of high quality pasture or supplementary feed is recommended.

Figure 2: Effect fat score at calving has on days to first heat

To increase conception rates, it is important to join females on a rising plane of nutrition.

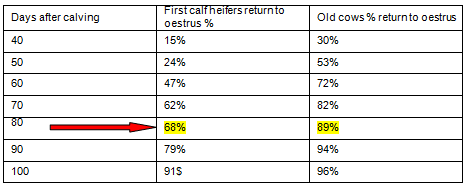

Table 4: Return to oestrus post-calving

Source: Merial Opportunity of a Lifetime

As Table 4 indicates, the real challenge in maintaining a 365-day calving interval lies with the heifer population. Only 68% of heifers are cycling within the 82-day period required to maintain the calving interval.

Important considerations for calving heifers include:

- first-calf heifers take longer to return to cycling post-calving

- heifers with dystocia take longer to return cycling

- heifers are particularly sensitive to body weight at calving and post-calving nutrition as reflected in slow return to oestrus

- aim for approximately 420–450kg liveweight at calving

- prioritise resources to meet the needs of heifers in the lead up to, and following, calving.

Heifers should be joined 2–3 weeks before the main herd as this allows 2–3 weeks longer to cycle post-calving and slot into the main herd to maintain the tight calving pattern. The downside is that these heifers have 2–3 less growing days to attain critical mating weight pre-joining, which means that monitoring weight gain post-weaning to joining is absolutely critical.

Heifer performance is critical. Underperforming animals are inherently less fertile, can fail to achieve maximum pelvic size leading to dystocia, and can fail to get into calf quickly as second calvers.

The effects of nutrition on reproductive efficiency in older cows is less apparent, and allows reallocation of the limiting factor in production, namely feed, to the younger cattle.

Select cows capable of conceiving within two mating cycles

In seeking to strictly maintain a 365-day calving interval, high culling rates may be required which in turn increases the number of replacement heifers required to maintain the herd breeding structure. This practice results in a higher proportion of quality pasture being used for maintenance of the breeding herd because of the amount of pasture needed to grow females up to first mating. However, the benefits of higher heifer retention rates far outweigh the perceived downside of having to allocate quality feed to breeders.

Purchase of in-calf heifers to maintain herd structure increases the risk of introducing infectious diseases, particularly pestivirus (also known as bovine viral diarrhoea virus or BVDV) or Johne's disease, and if heifers are from an unknown genetic background, they may not be compatible with strategic business and breeding goals. Purchased heifers are also unlikely to match the planned calving period and could have higher rates of dystocia than mature cows.

Biosecurity of individual herds is a serious consideration, and any introduction of outside stock can expose the herd to many animal health issues.

What to measure and when

- Conception rates from natural mating or when an artificial insemination (AI) program is implemented.

- Condition score of cows at regular intervals according to the seasonal conditions – monitor after weaning of the last calves, from 6 weeks before calving, and then from calving to mating.

- Liveweight of weaner heifers every 6 weeks until mating.

The stock manager should also observe the breeding herd for evidence of female activity (cycling) prior to the commencement of mating.

Further information

Further information on supplementary feeding can be found on the websites of state departments of agriculture:

- NSW Department of Primary Industries: www.dpi.nsw.gov.au

- Department of Primary Industries, Victoria: www.dpi.vic.gov.au

- Department of Primary Industries and Regions, SA: www.pir.sa.gov.au

- Department of Agriculture and Food, WA: www.agric.wa.gov.au

- Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania: www.dpiwe.tas.gov.au

Management of heifers and cows before calving

Guidelines for managing heifers and cows before calving

Careful management of nutrition of pregnant females in all trimesters of pregnancy pays dividends at calving time. Calf loss will be minimised and calving supervision can be kept to a minimum. Calving difficulties will be reduced by maintaining cows at condition score 3.0 (3.5 for heifers), supplying adequate nutrition from joining to calving to prevent growth restrictions to reaching maximum pelvic size. This requires maintaining a condition score of 3.0–3.5 through to the point of calving.

Manage pre-calving carefully to minimise difficulties at calving

If females go outside these guidelines:

- increase or decrease pasture available or pasture quality before calving to ensure condition score of cows or liveweight of weaner heifers remains within the guidelines. As a guide, manage British breed heifers to gain an average weight gain of 0.6kg/day to a joining liveweight of 300kg, condition score 3.0 at 15 months of age.

- consider supplementary feeding a high quality diet to cows when condition score is below the low 2s.

- consider supplementary feeding heifers, including a protein source rich in rumen non-degradable protein, particularly if pasture is readily available but quality is low. This ensures weaner heifers gain weight at 0.6kg/day to reach target weights at 3, 6 and 9 months post-conception, as defined in Tool 5.1.

- assess animal health status, particularly for internal parasites (worms and fluke tend to be a greater problem in younger animals), and correct if there is a problem, as described in Module 6: Herd health and welfare.

- achieve a balance required between:

-

- overfeeding (heifers in particular) in the last three months of pregnancy, as this will increase birth weight and subsequent dystocia

- underfeeding in the last trimester of pregnancy, as this will predispose to metabolic disorders like ketosis. Restriction of nutrition in the last trimester can increase dystocia rates, slow uterine contractions at birth, and delay return to oestrus post-calving.

Poor nutritional management of heifers and cows before calving can lead to a number of significant problems, including

- dystocia in heifers, due to inadequate pelvic size for the foetus, and due to over-fatness and uterine inertia in mature cows.

- birthing difficulties , which may lead to stillborn calves, inability of the mother to re-conceive, inability of live calves to thrive, reduced ability of resulting heifer calves to reach target weights at mating, and possibly reduced mature weights as cows.

- predisposition to various metabolic disorders, including milk fever (hypocalcaemia) and ketosis/pregnancy toxaemia (see Module 6: Herd health and welfare) due to over- and underfeeding of cows before calving.

What to measure and when

- Condition score of cows every two weeks from 12 weeks before calving.

- Weight and growth of heifers at 3, 6 and 9 months of pregnancy.

- Use Tool 3.5 of Module 3: Pasture utilisation as the basis for successfully matching seasonal pasture supply to the feed requirements of heifers.