4-Trait emphasis

Modify trait emphasis in line with individual herd requirements

The process of developing a breeding objective is an essential and very sound genetic improvement principle. Even taking the easiest and most practical approach of using an index developed by a breed society – and thus using the objective developed during the development of that index – will be a sound first step in designing a breeding program. But in all breeding programs, individual requirements will be brought about by differences in the production environment and markets, and personal preferences.

Breeders may require modification of trait emphasis to:

- minimise calving difficulty because of inability (extensive enterprise or difficult topography) or disinclination to handle calving difficulties

- improve temperament due to inability to handle flighty cattle

- meet market specifications of higher yield or different maturity types

- meet personal estimations of future market requirements (ie bulls selected today won’t produce sale progeny for at least 18 months, and 2–3 years in most cases).

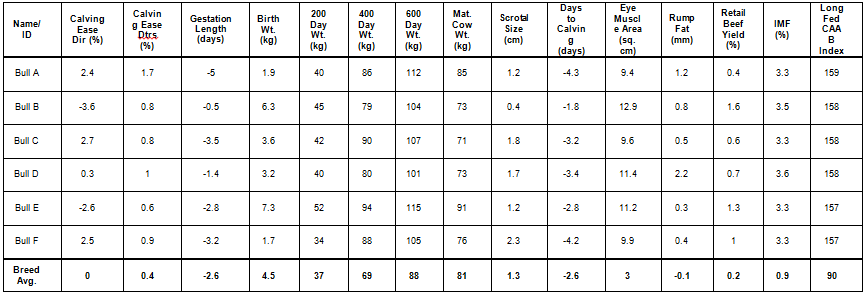

Special requirements can easily be catered for within the bulls that are high ranking on an index. Bulls may achieve high index values for different reasons, so applying an independent cut-off on individual traits will only marginally reduce progress towards a profit objective. For example, Table 1 shows that bulls selected with high indexes can have quite varying birth weight EBVs.

Some traits that are important to the breeding enterprise do not have EBVs, and therefore those traits aren’t included in the index. There is little option other than imposing independent culling on these traits, which include the structural traits (eg teats and udders).

Another decision point for control of the individual traits and for inbreeding is when allocating bulls to the mating groups.

When allocating bulls to mating groups, reduce the risk of inbreeding and dystocia and match traits, if required:

- Mate bulls with the highest EBV for calving ease to heifers, but remember that half of the genetics for calving ease comes from the maternal grand sire, so reducing calving ease may take more than one generation. Even older cows shouldn’t be mated to extremely high birthweight bulls because if you keep heifers resulting from that mating, they will carry genes for high birthweight.

- If possible, mate bulls from a breed with a lower mature size to heifers. (This is especially effective in a crossbreeding program where differences in mature size and hybrid vigour can cause increased birthweights, and therefore increased calving difficulties.)

- Match strengths and weaknesses of cow groups by allocating different sires. An example may be earlier maturing (low frame size) cows may be mated to later maturing bulls, or vice versa, if maturity type is important to your objective.

- Minimise inbreeding by preventing the mating of bulls with daughters or with cows that have a common parent (half-brothers and half-sisters).

What to measure and when

- Calving ease EBV for bulls allocated to weaner heifers, or birth weight EBVs when calving ease EBVs are not available.

- Male parentage of all cows in the herd. (Do this in age groups if individual identification is not recorded.)

- Monitor growth rates, turn-off age and turn-off fatness (see Module 7: Meeting market specifications).

- Monitor feedback from kill sheets and note any unwarranted trends that may need correction (see Module 7: Meeting market specifications).